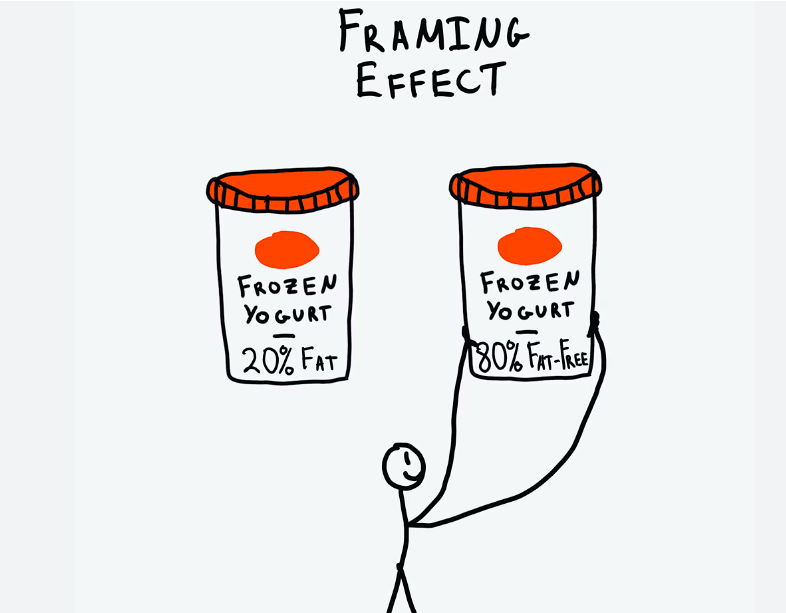

Games are composed by a string of decisions that players take, its this autonomy in fact that often differentiates movies from video games. However something that is rarely talked about is how as a Game Designer you can shift choices people make by framing things differently. This is called the framing effect.

Here’s a quote from Amos Tversky and Daniel’s Kakneman paper:

The psychological principles that govern the perception of decision problems and the evaluation of probabilities and outcomes produce predictable shifts of preference when the same problem is framed in different ways. Reversals of preference are demonstrated in choices regarding monetary outcomes, both hypothetical and real, and in questions pertaining to the loss of human lives. The effects of frames on preferences are compared to the effects of perspectives on perceptual appearance. The dependence of preferences on the formulation of decision problems is a significant concern for the theory of rational choice.

Amos Tversky, Daniel Kakneman

The quote above references a line of questioning pertaining to the loss of human lives, we’ll use this example to demonstrate this effect in practice.

Imagine that the U.S is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

- Program A: 200 people will be saved.

- Program B: ⅓ chance 600 people will be saved, ⅔ chance no people will be saved

Which one of these would you choose?

If you’re like most people (72%), then you would choose A.

The majority in this problem is risk averse, they would rather have the guarantee of saving 200 lives even when the other option has the same expected value (you can do this by multiplying the chances for the amount of people saved).

Here’s another set of choices:

- Program A: 400 people will die

- Program B: ⅓ chance nobody will die, ⅔ chance 600 people will die

Which one these would you choose?

In this case the majority of people would go for option B, people think that 400 guaranteed deaths are less acceptable than the ⅔ chance that 600 will die. This illustrates the following:

Choices involving gains are often risk averse and choices involving losses are often risk taking.

It’s easy to see that the two sets of choices above are identical (400 people will die = 200 people will be saved), the only difference in them is how they are framed.

These findings map onto the findings of Loss aversion, which were:

- People will take a sure gain rather than a gamble for a larger gain

- People will gamble to avoid a sure loss.

We’re starting to see the power of framing and how it can directly impact in-game choices, but the simplest is achieved by adding an offset to the gains and losses.

We can be sneaky and force a situation where it involves gain and another where it involves loss, and that will most likely influence the choice of the player, here’s an example:

You are given $1,000 (There you go, just like that). Then you are asked to choose between:

- Option A: 50% chance of winning another $1,000.

- Option B: A guaranteed $500.

If you have been following the logic of the studies above, you can guess that most people here go to option B.

Here’s another example.

You are given $2,000 (even more this time around, it’s your lucky day). Then you are asked to choose between:

- Option A: 50% chance of losing $1,000.

- Option B: You must lose $500.

Most people here would choose A.

By now you also know that the two sets of options are identical just like the experiments above, so what’s the difference?

Well we framed the first set of options in terms of gain and the second in terms of losses, just by giving an initial offset to where the player starts monetary wise. This effectively means that depending on how you want your games to function you can change the framing, do you want players to be more risk averse when engaging with your mechanics or more risk taking?

Let’s get more practical though, what are examples of this in actual video-games?

I’ll use one of my favorite games, League of Legends and its DOTA2 counter-part. Specifically, I want to talk about how deaths work in both games.

In League of legends if you die you don’t lose anything, your punishment is waiting on a timer, however the person that killed you gets gold and experience, this essentially means that Riot Games framed things in a positive way rather than a negative one.

As the dying player you’re not punished more than the death timer, as the killer you get positively rewarded. This mirrors many of the more recent board games where destruction is on a separate “track” that doesn’t directly penalize the player.

You can think of Settlers of Catan vs RISK, where in one there’s no way for you to lose progress on the cities you’ve already built versus the other where you can end the game much weaker than how you started.

League of legends follows the same pattern, you never end the game any weaker than you were before.

Now looking at DOTA2 they went a different route, they framed things in terms of losses. They maintained the logic that the killer gets gold and experience but the killed champion also loses gold. This could be one of the reasons that the general audience around both of these games considers DOTA2 more punishing or hardcore. Framing is important.

Does this mean that what DOTA2 did was a bad design choice?

No, like with every design choice there’s positive and negatives. In this case DOTA2’s choice lands them with an interesting choice of “push-your-luck”, where players are constantly evaluating if they should stay in the map longer to get a better item once they go back to base or risk losing gold if they die. This however does mean that the game is less accessible than League.

Hopefully this will make you consider more closely how you create systems and mechanics in terms of losses and gains to get the intended original behavior out of the player!

Leave a comment